Parau & Abot (foreign ships & boats)

The word parau in the Tolai language means ‘foreigner.’ I learned of this word during a research trip to Rabaul in 2018. This word parau came up in a conversation as I was passing through a location between Rabaul and Kokopo called Tungparau. Tung is a grave. The foreign graves referred to at Tungparau are Fijian men who met their fate, as catechists for the Wesleyan Methodist missionaries. The Fijians who were killed by Tolai people are presumably buried at this location. The onset of Europeans and other foreigners occupying land in and around Rabaul resulted in many escalating tensions. The early years of European contact with the indigenous people of New Guinea islands were hostile and far from romantic with violence, bloodshed, and retaliation on both sides in negotiating significant impacts of social, cultural, and spiritual change to indigenous societies and values. The view from Tungparau is high above the sea and looks out over the na ta - deep ocean waters of Rabaul harbour. Whilst at Tungparau, I also learned that the word parau later became the word for ship, foreigners ship.

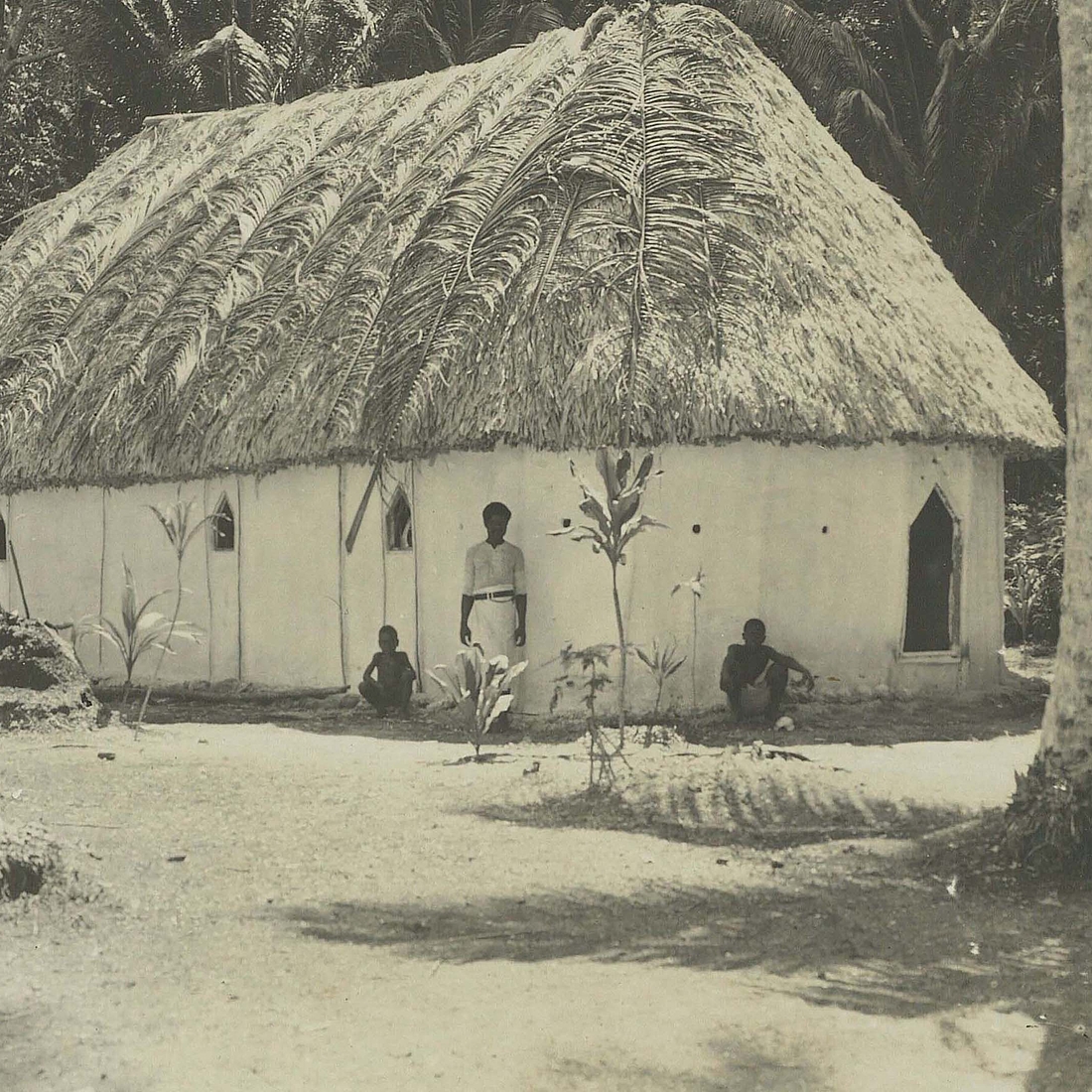

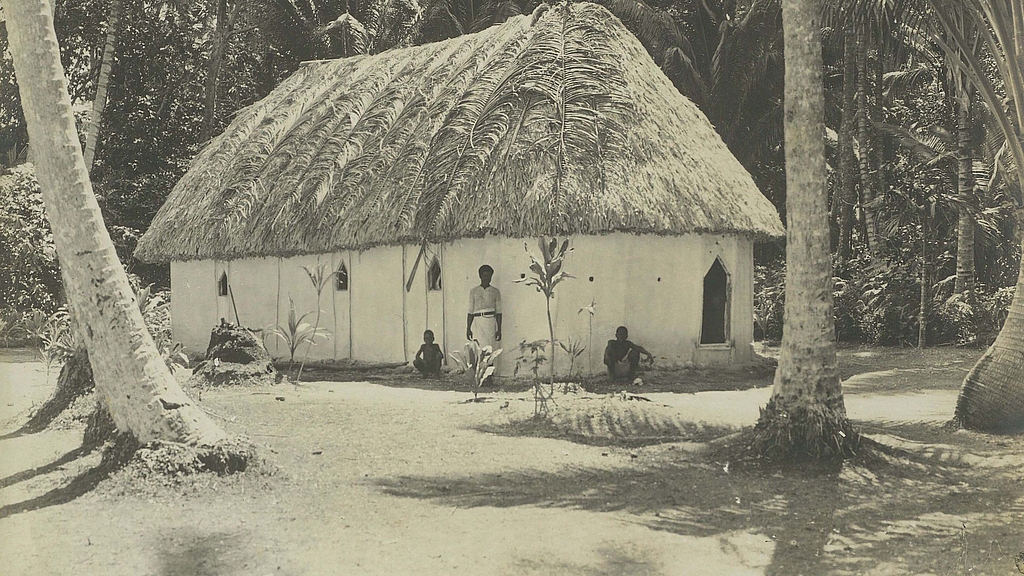

Historically, some of the earliest parau (foreign ships) navigated the New Guinea islands in search of whales, establishing some of the earliest trading relationships between indigenous New Guinea people and Europeans. These trading relationships according to Alistair Gray’s research in the Bismarck Archipelago (1999) were largely determined on existing ship log records indicating the ‘friendliness of natives, safe anchorage and abundant supply.’ Port Hunter, Duke of York Islands was one such location that was frequented by whaling ships, due to the supply of ‘ample fresh water.’ Interestingly, Port Hunter was the same location where Reverend George Brown, the first missionary, arrived with eight Fijian teachers. They arrived in August of 1875 on a steamship and sang hymns for three days and nights aboard their parau, before venturing onto the shore, eventually building the first Methodist Church in the same harbour. (Image 1)

Lisa Hilli | NDL-Blog | 02.12.2021

Die erste Wesleyan Methodist Church, Port Hunter, Duke of York Islands, Fotograf unbekannt, Karl Nauer Fotoalbum, CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 - Südsee-Sammlung Obergünzburg

Otto Finsch’s survey of the lands and islands of New Guinea in the steamship Samoa in 1884 and 1885 was navigated by ‘merchant marine, the captain Eduard Dallmann from Blumenthal near Bremen, famous for his lucky trips as a whaler in the Pacific.’ Finsch’s trips in the Samoa was funded by a German secret commerce council of bankers and given specific instructions by the head of this council to ‘locate harbours, establish friendly relations with the natives and acquire land to the greatest extent’, enabling the establishment of a profiting business enterprise, the New Guinea Company, under the guise and declaration of the Protectorate of German New Guinea. The 1884 annexations of the lands of ‘Papua’ and ‘New Guinea’ were decided upon by foreign people in foreign lands, without consent by the people of Papua and New Guinea. The German colony of New Guinea essentially was a business enterprise and the local indigenous communities an available source of cheap and exploitative labour supply.

Expanding upon and monopolising this source of Melanesian labour under a policy of the German New Guinea Protectorate was the trading firm Deutsche Handel-und Plantagengesellschaft (D.H.P.G.) With several established copra plantations in German Samoa, approximately 7000 Melanesian people from across and beyond the Bismarck Archipelago were recruited as indentured labourers by the D.H.P.G. from as early as 1867, with some of the last recruits returned by ship to Rabaul as late as 1921, when New Zealand assumed administrative control of Samoa post First World War.

I had always known that Tok Pisin (Melanesian Pidgin English) was born from the copra plantations in the colonial Pacific. What I didn’t know was that Melanesian Pidgin may have originated as Samoan Plantation Pidgin as defined by linguist Ulrike Mosel (1980). According to historian Malama Meleisea (1976) ‘each shipload of recruits comprised groups of wantoks or men from the same language area, so that while each individual had a small group of fellow language speakers to keep him company, communication between groups was difficult.’ The D.H.P.G. had a station in the Duke of York Islands, where recruiting schooners would depart and return with mostly Melanesian men, adolescent boys and infrequently women. This small island archipelago, yet again became an abundant supply for parau, and a temporary harbouring place of Melanesian bodies ready to board German vessels in preparation for direct sail to Apia Samoa. Once in Samoa, labourers were allocated jobs based on their age, strength and ability for the duration of a three year contract. Melanesian labourers working in German Samoa plantations were paid only in food rations and loin cloths. (Images 2 and 3)

D.H.P.G. schooner Samoa off Apia Samoa with the last Melanesian recruits 1913, Karl Hanssen album Gessa Akerman-Ohle Collection via Tony Brunt.

Tightly packed lighter with mostly Solomon Islands men at the D.H.P.G. shipyard, Sogi, Samoa 1913. Karl Hanssen album Gessa Akerman-Ohle collection via Tony Brunt

My initial curiosity of Melanesian people in Samoa was sparked by a personal photograph shown publicly by historian Tony Brunt, depicting a very young unnamed Melanesian girl attending to 17 year old Samoan woman, Miss Fusipala Maryanne Easthope in Apia Samoa 1909. This led me to ask the New Guinea Islands community via social media “If anyone had any oral histories and or personal accounts of ancestors working in German Samoa plantations? And did they come back?” Some did, most didn’t for several reasons. Wenzel Esekia commented “my great grand uncle ToGilam of King left the shores of Kandas. He never returned home.” Philip Kurivo replied “I knew an old man from my village who returned from Samoa. [His name was Sika] He used to sing Samoan songs and do Samoan dances.” Some labourers were returned to the wrong island, causing dislocation, broken genealogical histories and connections to their homelands. A Melanesian woman came forward and stated “I am a descendant of one of the child[ren] that was brought back with the people of Mussau in New Ireland from Samoa. My grandfather and his sister were not from PNG and was brought here [PNG] by the men while returning from the Samoan plantations. I’ve always wanted to learn more about the history. PIKO was his name and his sister’s name is Perilla. The only identity they had was their names.”

Children such as Piko and Perilla, born of Melanesian men and Samoan women associated with D.H.P.G. plantations in Samoa are collectively known in the Samoan language as Tama Uli black man and Teine Uli black woman. According to Asenati Liki’s research (2007), second and third generation descendants of Tamu Uli and Teine Uli live in both Samoa and New Zealand today. Stories of descendants of Melanesians who did return home is rare, largely undocumented, and untold. Another Tolai man responded to my question, “Most Tolai oral history is hidden in songs” This was confirmed by Wes Waninara “Listen to any “Abot” songs from New Ireland, Duke of York and the Gazelle Peninsular, the lyrics provide hints of places travelled, longing to be back home. Most of the “Abot” songs sung by famous bands such as Barike, Painim Wok, Narox, Leonard Kania, Junior Kopex were probably composed by people who travelled in boats (abot) to Samoa and other places and eventually came back home. The lyrics of these songs will provide great insights.” Most Abot songs are sung in the plantation language of Tok Pisin, one of three Papua New Guinean national languages today. A few are sung in Tinata Tuna (Tolai language). If you understand either of these languages, I’ve compiled a YouTube playlist of some Abot songs by Papua New Guinean musicians. Further research and context are needed of Abot songs to decipher the true meanings and hidden histories, relating to New Guinea Islands community.

Similar research of Asian and Pacific labourers brought to work in the colony of German New Guinea, with a particular focus on Norddeutsche Lloyd (North German Lloyd) ships may produce similar insights as described here, particularly with Rabaul being home to the largest Sino Niugini (Chinese-New Guinea) population in all of Papua New Guinea. Melanesian community members who are seeking more information about their ancestors who worked in German Samoa can access the ‘Deutsche Handel-und Plantagengesellschaft: Registers of Melanesian Indentured Labourers in Samoa 1887 – 1913’ This list of labourer’s names can be viewed via microfilm PMB 2004 . If you’re in Australia, you can request this list from the National Library of Australia in Canberra. If you’re in New Zealand get in touch with the National Library of New Zealand. The original register list is held in the Nelson Memorial Library in Apia Samoa. I intend to get a copy of this list and would be happy to share this information with descendants in a sensitive manner.

Please get in touch with me via my email Lisa.Hilli@dsm.museum or you can message me directly on Facebook @Lisa Hilli.