North German Lloyd in the Colonial Era: A Search for Traces in the German Maritime Museum

The ongoing research project on the role of maritime infrastructure and collector networks, with a focus on Norddeutscher Lloyd in the Western Pacific during the German colonial period, calls for rethinking the colonial heritage of museums at the Deutsches Schifffahrtsmuseum (DSM) / Leibniz Institute of Maritime History as well.

Researching museum collections and archives requires a great deal of detective flair. Often, documents, objects, and materials in modern collection management systems are not keyworded as would be desirable for current research questions. This is also true for colonial history research at the DSM: since it has only been open to the public as the National Maritime Museum since 1975, some objects, written works, and archival materials from the empire or related to its colonies entered the museum's library and stacks significantly later and possibly through many hands. Classical contemporary entry lists, which at least conditionally assigned objects to their colonized regions of origin or reference, are rarer there in this form. In general, unlike cultural objects that arrived in German museums from non-European societies and not infrequently under questionable circumstances, their involvement in colonial issues does not result from their origin alone. German maritime history and its objects are still far too often clinging to narratives of inventiveness, adventurousness, and thus pure narratives of progress. This is a postcolonial problem, because it divorces many of the objects in the DSM in the supplement from their original contexts of use.

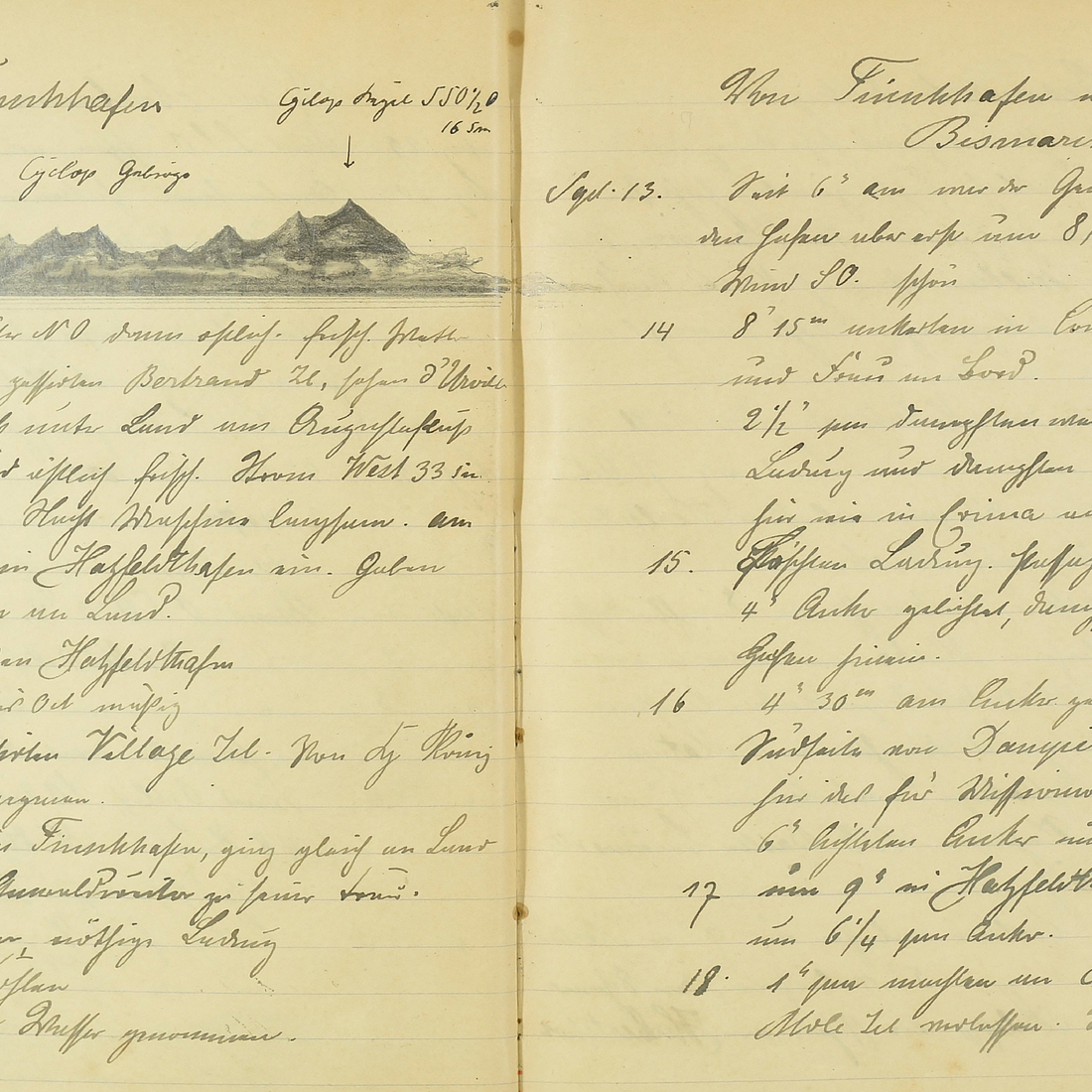

Ships and shipping may not always be colonial per se, but they often become so through their contexts. Whenever people enter into a relationship with one another through or via maritime use, whenever political, social, cultural, or economic dependencies arise, maritime historiography must also allow for critical readings. This applies, for example, to reception material, that is, that which consciously or unconsciously reflects colonial contexts. A second look at some of the things in the DSM is worthwhile: If you look at captain's diaries at the DSM, for example, such as the one from the steamer YSABELL from the years 1890/91, you will discover a multifaceted part of German maritime history told at first hand. The steamship, built by Blohm & Voss in Hamburg, performed its island service in the so-called protectorate of the Berlin New Guinea Company, in which the interests of German merchants and investors in the western Pacific had been secured by the German Empire since 1884. Ships like this brought local societies into contact with the Europeans traveling on them.

On the one hand, there are personal curiosities, for today's viewers remarkable coastal drawings of maritime realms still quite unknown to Europeans, entertaining accounts of everyday life on board along uncertain coasts. They tell of braving tropical fevers and many discoveries - classic, fondly told seafaring stories. However, they also reflect the fates and experiences of numerous unnamed colonists who were recruited to work by ship under questionable conditions. Some of them tried to escape and other stories tell of excessive punitive expeditions including retaliatory killings of segments of the local populations. Captain Schmieder's diary from aboard the YSABELL provides a first-hand example of how German shipping in the Pacific, European knowledge history, and unequal, sometimes violent, power constellations were inextricably linked in the colonial context. [Figure 1]

Tobias Christopher Goebel | NDL-Blog | 20.08.2021

Image 1: Captain Schmieder's diary from aboard the YSABELL. Photo: DSM / Archiv

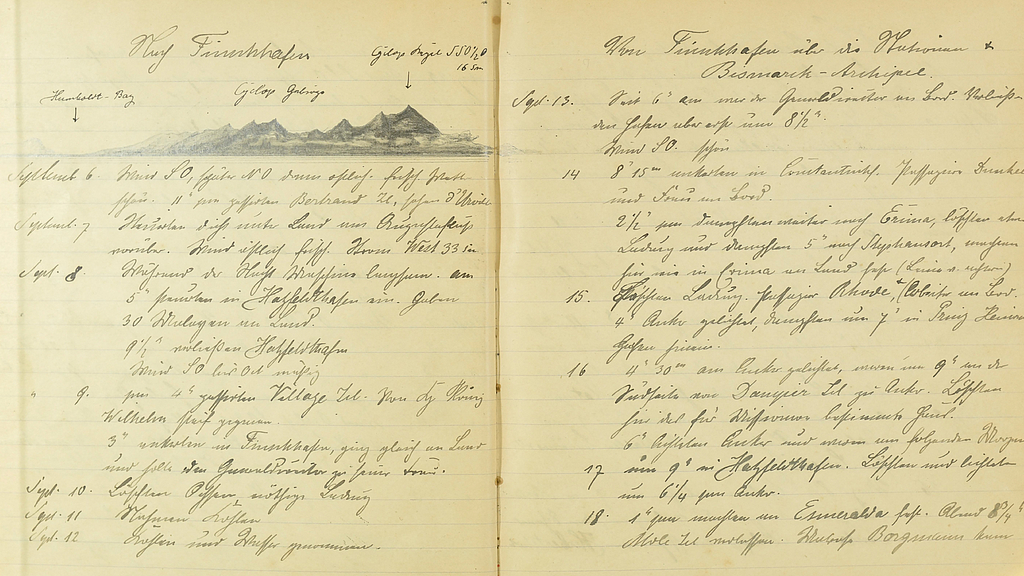

All these aspects of German shipping history in the 19th and 20th centuries did not take place in a vacuum and on the vastness of supposedly masterless oceans. They are closely linked to the ideological views of an expanding society that, according to its self-image, divided the world hierarchically into civilized and uncivilized peoples. Interestingly, this was reflected even in the ship's hold: The SUMATRA of Norddeutscher Lloyd, which also performed island service in the years before World War I, was explicitly equipped with two kitchens even in the construction plan: one for the white crew and passengers and a so-called "Chinese kitchen." People from East Asia and Southeast Asia were imported to the South Sea colonies as laborers, preferably taking on unloved tasks such as those of coal trimmers on the steamships. This job, under hardly acceptable working conditions, was reluctantly given to Europeans in tropical climes. [Image 2]

Image 2: The SUMATRA of Norddeutscher Lloyd, which also performed island service in the years before the First World War, was explicitly equipped with two galleys even in the construction plan. Photo: DSM / Archiv

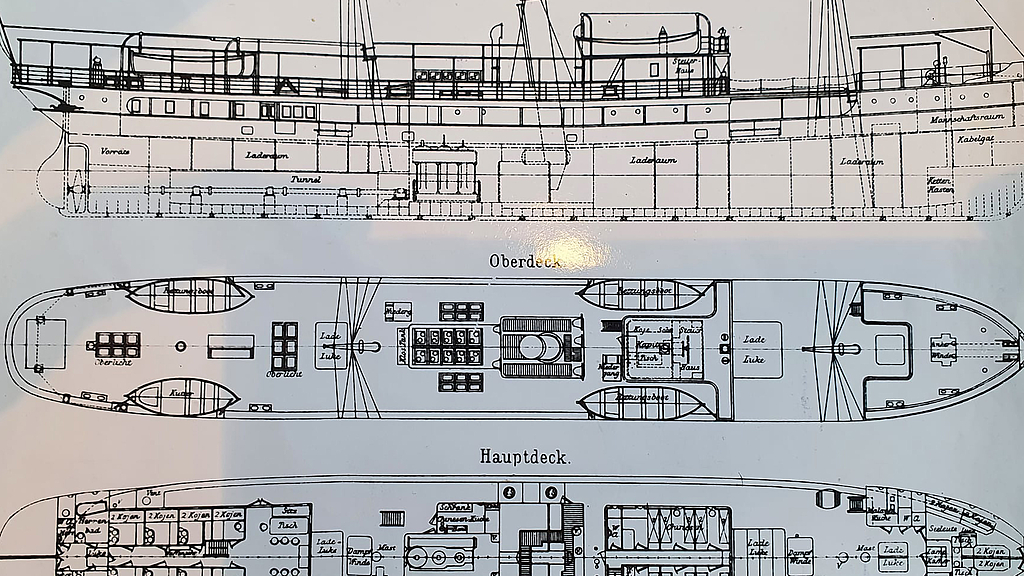

Emerging structures and colonial practice on the ground interacted closely with discourses in the colonial metropolis. As time went on, the German colonial administration increasingly sought to nationalize transport links. For Norddeutscher Lloyd, which served as an infrastructure partner for the imperial mail steamer service to Australia, East Asia and the Pacific, the German protectorates in the South Seas remained only a small part of the overall entrepreneurial complex. However, this says next to nothing about the people who lived in the colonial context or whose way of life was determined. From the perspective of the colonial administration, planters, merchants and missionaries, on the other hand, the maintained shipping lines constituted the everyday functional element of the colonial state that was essential for survival. Only through regular shipping could dependency relationships between Pacific and European societies be permanently established. According to its own publications, the company set out to be "a link connecting nations" and claimed "international significance. Prestige and exoticism were communicated, but hardly the actual conditions on the ground. [Fig. 3]

Image 3: Prestige and exoticism were communicated, but hardly the actual conditions on site. Photo: DSM / Archiv

When we deal with collections and cultural objects from provenance contexts with North German Lloyd in the museum collections in the coming weeks and months, the aim will be, in a postcolonial sense, to make lesser-known collection contexts and their collectors visible and at the same time to question the epistemic foundations and contexts of these collections. After all, maritime trade routes were the heartbeat of the structural translocalization of cultural goods.